For some reason, of all the ships that have sailed the oceans, it’s the unlucky ones that capture our imagination. Few ships have been as unlucky as the RMS Titanic, sinking as she did on the night of April 15, 1912 after raking across an iceberg on her maiden voyage, and no ship has grabbed as much popular attention as she has.

During her brief life, Titanic was not only the most elegant ship afloat but also the most technologically advanced. She boasted the latest in propulsion and navigation technology and an innovation that had only recently available: a Marconi wireless room, used both for ship-to-shore and ship-to-ship communications.

The radio room of the Titanic landed on the ocean floor with the bow section of the great vessel. The 2.5-mile slow-motion free fall destroyed the structure of the room, but the gear survived relatively intact. And now, more than a century later, there’s an effort afoot to salvage that gear, with an eye toward perhaps restoring it to working condition. It’s a controversial plan, of course, but it is technologically intriguing, and it’s worth taking a look at what’s down there and why we should even bother after all these years.

Wireless as a Service

When Titanic‘s keel was laid down in 1909, commercial radio was in its infancy. The Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company, popularly known as the Marconi Company after its founder, Guglielmo Marconi, was established mainly to provide wireless telegraphy services to ships at sea. It had only been in business for twelve years at that point, and had only been installing “Marconi Rooms” in ocean liners since 1903. Before Marconi, once a ship was beyond sight of land, it may as well not have existed. Radio changed all that, and the lifesaving potential of being able to send a distress signal was used by shipping lines to justify the expense of adding a Marconi system to a ship.

In practice, though, safety of life at sea was a secondary consideration in including wireless telegraphy into the design of ocean liners. The Marconi Company was a commercial venture, and as such needed to monetize their service to the greatest extent possible. Sending messages back and forth to other ships or using the system to contact shipping agents on shore to arrange berthings were important use cases, but not terribly profitable. Catering to the whims of well-heeled passengers, however, many with the desire to flaunt their wealth by sending a “Marconigram” from the middle of the Atlantic was very profitable. It cost 12 shillings and 6 pence for the first 10 words, the equivalent of $63 dollars in 2017.

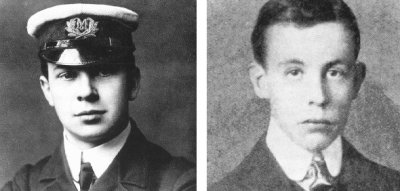

The Marconi service proved so popular that in the first 36 hours of the crossing that Titanic‘s two radio officers, Harold Bride and Jack Phillips, sent approximately 250 Marconigrams to shore stations in the Marconi network. The young men, 22 and 24 respectively, worked long hours to service the demand, made worse by a failure of the brand new radio gear – it had only been installed a week before sailing – the day before the collision. The two stayed up all night diagnosing and repairing the problem, which was a violation of Marconi Company policy, but showed considerable dedication to their employer.

State of the Art

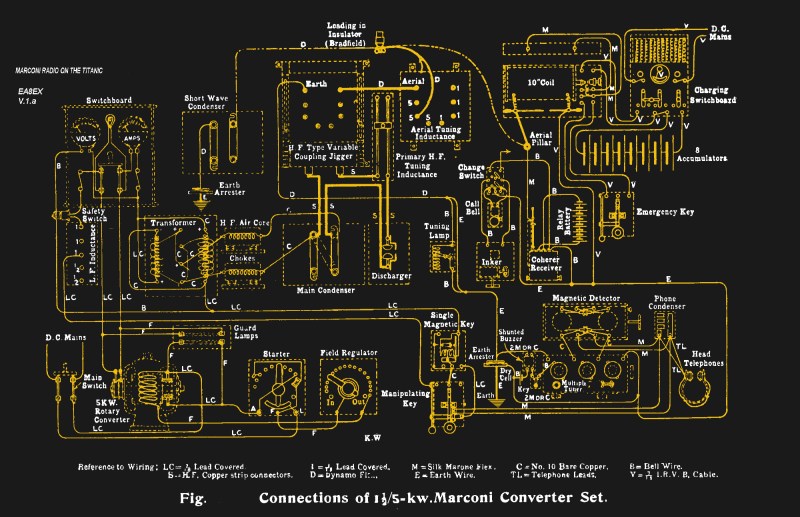

The Marconi suite on the Titanic was relatively spacious. It consisted of three rooms: the main room for the operator, a “Silent Room” with soundproof walls to house the loud spark-gap radio gear, and a small bunk room for the Marconi operators. The suite was located on the boat deck between the bridge and the Grand Staircase of the First Class entry. It was located as close to the top of the ship as possible to keep the feedline run to the antenna as short as possible.

The radio gear consisted of a motor-dynamo generator that boosted the ship’s DC electrical supply to high voltage AC to power the synchronous rotary spark-gap transmitter. At 5 kilowatts, the transmitter was the most powerful on the sea, and capable of reaching New York or London from the middle of the Atlantic. International convention called the use of the 600-meter band for ship-to-shore communications, and the 300-meter band for ship-to-ship work.

A Night to Remember

Beginning on April 14, ships in the area off Newfoundland began spotting icebergs. As was common practice, radio-equipped ships would broadcast warnings of the floating mountains, to warn other vessels of the danger ahead. No fewer than six messages warning of icebergs were received by the Titanic‘s Marconi operators. The first two of these messages were relayed to Captain Edward Smith; the last four, however, were never brought to his attention. It is speculated that Bride and Phillips were so busy servicing the backlog of Marconigrams caused by the outage that they never relayed the messages to the bridge. That’s supported by Bride’s response to the last warning from the SS Californian: “Shut up, I am working Cape Race,” referring to the Marconi relay station at the southern tip of Newfoundland. That final warning was received at 23:30 ship’s time, a mere nine minutes before Titanic‘s death blow.

Whatever role Bride and Phillips’ deference to their employer’s business played in causing the disaster, their response to it and the raw power of their gear and their skills as telegraphists made up for it. Without the wireless, there’s little doubt that the loss of life would have been even greater than it was. Titanic stayed on the air for almost all of the two and a half hours it took for her to finally go under, and Bride later testified that Phillips was still transmitting as they heard water flowing up the deck outside the Marconi suite. Both Bride and Phillips made it into the frigid North Atlantic before the bow section slid under and got into the last lifeboat; Bride survived with only minor injuries, but Phillips died of exposure during the long wait for RMS Carpathia, responding to the distress call that he himself had hammered out only hours before. The 705 lives that were saved that night were saved because they stayed on the job, despite being relieved by Captain Smith.

It’s Not a Ship. It’s a Tomb

Titanic‘s secrets, and her dead, lay hidden beneath the Atlantic for almost three-quarters of a century. Once Robert Ballard found the wreck in 1985, it stirred something in the collective imagination, and spawned an entire industry of Titanica. Subsequent explorations of the wreck have mapped out in exquisite detail the location of every inch of the ship and every artifact’s location, and multiple items have been recovered by remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) over the years.

The Marconi suite’s location at the top of the ship was fortuitous, as the bow section of the great ship settled to the seafloor in essentially an upright position. This makes salvage of the gear, which can be seen in the video below, technically possible. RMS Titanic, Inc, an Atlanta-based company that has the sole right of salvage over the wreck, has recently received permission in US District Court in Virginia for the “surgical removal and retrieval” of the Marconi gear from Titanic.

The wreck is protected by a treaty between the US and the UK, which has so far limited salvage to items in the debris field surrounding the wreck. The retrieval of the radio, which will require cutting away a section of the suite’s roof, will mark the first time the wreck has been plunged for its treasure. The argument put forth is a sensible one; that the steadily deteriorating structure of the ship will soon lead to a complete collapse, burying the Marconi gear under tons of corroded metal and rendering it lost to the ages. Others argue that this will be an act of grave robbery, a desecration of the final resting place of 1,527 victims of that fateful night.

Whatever your position, it’s hard to deny that the recovery of such an important artifact, one that both cost so many lives and saved many too, is a tantalizing idea, and one that should prove very interesting to watch unfold.

via Radio Hacks – Hackaday https://ift.tt/2Tpk6GV

No comments:

Post a Comment